As many reading this can, I’m sure, attest, if one pursues family history long enough, sooner or later one runs out of stories touching on direct ancestors, and one starts to fan out in search of other subjects of curiosity and mystery, touching increasingly distant relatives.

And then, I think, a transition of sorts occurs, or can occur, from pursuing stories that have indeed been steadily retold, and really weren’t in any great danger of being tossed to the wayside, to ones that actually have been forgotten, truly lost, and now need finding once again.

This story hits both of those notes: it touches on a family not my own, at least by any blood reckoning, and to the best of my knowledge, it represents the reanimation of names and events that – like a beautiful Roman mosaic lying beneath a British farmer’s field – have been silently waiting, for years, to come back to light.

Standing back from it all, this inquiry can basically be summed up as an attempt to fit together four clusters of puzzle pieces, four collections of individuals from separate eras. To join these pieces together would be to recover the unbroken lineage.

The family involved is French, hailing originally from the Alsace region, then extending to Paris at the height of the Terror and later during the rise of Napoleon, and – following a kindhearted adoption – coming to rest in Pennsylvania. I’ve thought about how best to introduce these puzzle pieces. There are many possibilities, but the easiest way may be the order in which I discovered the information itself. Here is the outline I’ll follow:

- Puzzle piece cluster No. 1

- Puzzle piece cluster No. 2

- Puzzle piece cluster No. 3

- Puzzle piece cluster No. 4

- Joining the pieces (however tentatively)

Puzzle piece cluster No. 1: The Adoption, at Age 13, of Pauline Gertrude de Fontevieux

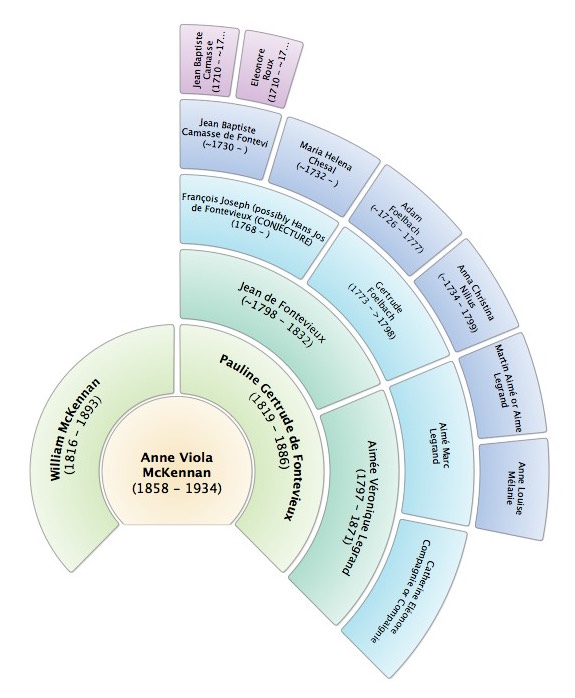

Several months ago, looking at a fan chart of my sister-in-law’s ancestors, I realized there was a large pie-shaped gap above one name, her 3rd great-grandmother: Pauline Gertrude de Fontevieux. (For anyone who has spent much time in an obstetrician’s office, these areas of ignorance on fan charts appear not unlike acoustic shadows on fetal ultrasounds. Beyond this point, moving out and back in time, who knows? An expanding wedge of genealogical darkness.) But in addition to the obvious lack of data, parents, etc., there was her surname. De Fontevieux. Not your everyday moniker. All the other immigrants in our extended family, including my sister-in-law’s, were either English, Dutch, Irish, German, or eastern European Jewish. French nobility? That would be distinctly “new.”

I didn’t have to go far to learn that Pauline Gertrude (de Fontevieux) McKennan spent her life as the wife of a prominent Pennsylvania judge, William McKennan (1816-1893). She bore a large number of children, who in turn took their places in mid-Atlantic society.

Her obituary describes a life of quietly principled giving to others.

It reads:

Mrs. Pauline KcKennan, wife of Judge McKennan, of the U.S. Circuit Courts, died Friday night at 10:30 o’clock, at her home on East Maiden street, Washington, Pa. She was a noble woman, always foremost in good works for the community. She was intensely patriotic and during the [Civil War] was widely known as the promoter and active helper of every effort on behalf of the soldiers. A friend of everyone to every class and condition her death is mourned in all circles…

But that’s the very end of the story.

Here’s where it begins…

As a girl, so we are told, Pauline Gertrude had been “found” as an “orphan,” by the American educator Emma Willard, in Paris, and brought back to America to receive her education and upbringing at Willard’s school. Willard is said to have been enchanted by the young girl’s unusually beautiful singing voice, something people at several stages of her life remarked upon.

If you’re having trouble making out the first paragraph, it reads as follows:

De Fontevieux, Pauline Gertrude,

Was born in France.

On Mrs. Emma Willard’s visit to France in 1832, she met in Paris this little girl, then eleven years old, to whom she was greatly attracted. The child was an orphan, bright, pretty, and unusually engaging, possessing withal a voice remarkable for its sweetness. Mrs. Willard conceived the idea of bringing her to America, and giving her such education as Troy Seminary could offer. The consent of the guardian being obtained, Mrs. Willard assumed the responsibility of her future. For eight years she was a pupil in the Seminary, where she received a musical training that developed her fine voice, and qualified her to instruct others. In 1840 she went as teacher of music to the Seminary in Washington, Pa., under the management of Miss Sarah R. Foster, a former pupil of Troy. At the end of two years Miss Fontevieux married Mr. William McKenna[n], a young lawyer…

This article on Emma Willard’s semi-adoption of Pauline Gertrude is remarkable for two things. It calls her an orphan, and it offers no mention whatsoever of her parents, or what had happened to them.

Before I move on, I also found this mention of her from 1841.

The posting for the winter term of Willard’s school advertises Pauline Gertrude’s role as an assistant teacher, promising:

[t]he latter being a native of France, will be able to communicate the correct pronunciation of the French language.

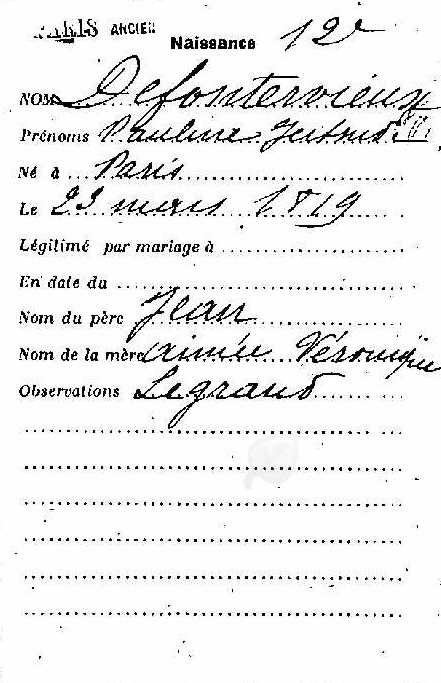

And then I found these recollections by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the future suffragist.

A transcription:

“…I recall the orphan whom Mrs. Willard adopted and brought back from France to educate in Troy Seminary. She was a charming little girl, De Fontevieux by name. She had a lovely voice, and she and I used to sing together….”

These small clippings help me to imagine just a little of the world this girl had been thrust into, and what a vibrant, buoyant survivor she must have been.

Puzzle piece cluster No. 2: The Parisian Couple— Jean de Fontevieux and Aimée Véronique Legrand

Let’s move to Pauline Gertrude’s parents.

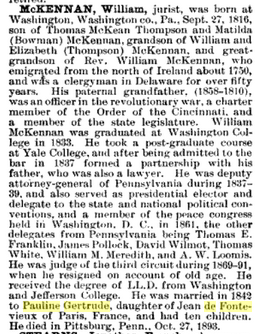

Continuing with this first superficial round of searching, I soon located a biography of Pauline Gertrude’s husband, the judge, full of the usual allusions to the college he attended and the societies he had been a member of, but, buried at the end, was the one thing I had been looking for.

The last few lines in the above excerpt are key:

“He was married in 1842 to Pauline Gertrude, daughter of Jean de Fontevieux of Paris, France, and had ten children.

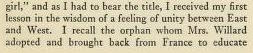

I had the father! Taking my curiosity over to a well-known genealogy site, I almost immediately lucked out in finding several documents from the Parisian bureaucracy, c. 1820. One of these was Pauline Gertrude’s birth certificate, or the close equivalent.

Evidently, she had been born two years earlier than the year she told everyone in America, in 1819, to Jean de Fontevieux, and his wife, Aimée Véronique Legrand.

More searching, and I soon located similar documents relating to two of her brothers, and after some time on another genealogical site, a resource I’ve found particularly helpful with European trees, I had two more siblings who had gone on to found families with multiple offspring surviving well into the 19th century, who were now scattered across France. One of these children, a boy, grew up to become a soldier who was awarded the Légion d’honneur.

In order to keep this relevant and on track, I’ll omit those aspects of the story. Suffice to say, though, at this point the family tree was starting to fill out.

I also soon found at least a couple of generations of Pauline Gertrude’s mother’s family, the Legrands. Not a huge number, but enough for some future researcher to go on. (I’ve included those names as part of a fan chart at the end of this post.)

Back to those Parisian documents. It seems that in 1831 Jean and Aimée Véronique were married in a ceremony in Paroisse Saint Médard. Note that by this point they had already had numerous children, all of whom had taken Jean’s surname de Fontevieux. I wondered, had their relationship been a common law union? Or, had they married previously, but simply decided to renew their vows? Impossible to say.

At any rate, marry they did, and within a year, Jean was dead. I could not find a cause of death.

Looking at the date, this was clearly an event that had only just occurred at the time of Emma Willard’s 1832 trip to France, and her almost immediate adoption of Pauline Gertrude.

One can imagine: a grieving family, having lost their father, wondering how to find a way forward… Enter the wealthy American proto-feminist teacher offering to help, at least in regard to the fate of the oldest sister. A hard thing to say “No” to an offer like that.

As it turns out, Pauline Gertrude wasn’t an orphan at all, at least according to the classical definition of the term. Her mother, Aimée Véronique, was still very much alive, and died many years later, in Verberie, a town in Oise where her other daughter, Gertrude Joséphine (de Fontevieux) Rebours, had ties. So what had happened? Why had all involved felt the best thing was for Pauline Gertrude to leave France and go to America with Emma Willard? And why had there been a guardian involved (per the bio I excerpted)? We may never know.

At any rate, from Jean’s marriage certificate, we learn that his father was named François de Fontevieux and his mother was Gertrude Foelbach.

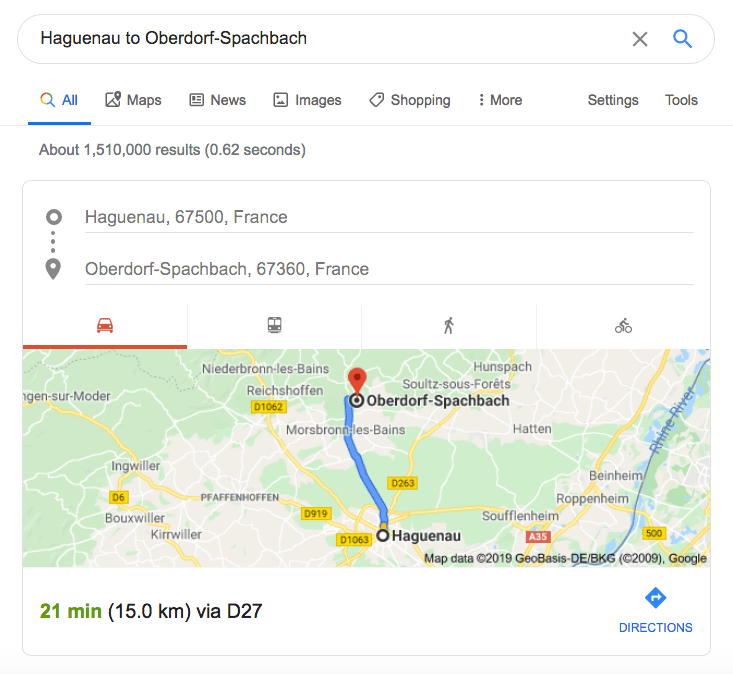

Two more points: 1) Pauline Gertrude was named, at least partially, after her paternal grandmother, and 2) on his death certificate, dated 1832, Jean’s place of birth is listed as what looks like “Oberdorf.”

Here’s an enlargement:

Looking through a list of French place names, one likely candidate comes up in the Alsace region: Oberdorf-Spachbach.

Make a mental note of that, as it’s important and I’ll come back to it.

Puzzle piece cluster No. 3: François de Fontevieux and Gertrude Foelbach

We just learned that the parents listed for Jean de Fontevieux on his marriage certificate were François de Fontevieux and Gertrude Foelbach (evidently also spelled Fülbach).

Interestingly, I found mention on FamilySearch of a marriage between one “Hans Joseph de Fontevieux” and a “Gertrude Foelbach.” The couple married 31 Aug 1796, in Kadenbach, Hessen-Nassau, Preussen/ modern-day Germany. It was a relationship that was added by FamilySearch several years ago, with no source and no accompanying image.

As an aside, after painful trial and error, I have to say I’ve come to distrust the handwriting interpretations of American volunteers in reading French and/or German civil documents. The record may well have said “Hans,” but experience tells me to take that with a large grain of salt; it could also have said something else entirely. The possibility of a mistake in transcription will come into play at the end, as I attempt to put all this together.

At any rate, in addition to the above, there are also trees on both FamilySearch and Geni recording that same union, “Hans Joseph de Fontevieux” marrying “Gertrude Foelbach,” and purporting to supply the extended family of Gertrude. If these two trees are accurate, this particular Gertrude Foelbach was evidently the daughter of Adam Foelbach or Fülbach (1726-1777) and Anna Christina Nilius (1734-1799), who together had nine children. (Descendency chart here.)

Now, one might object: “But we’re not looking for a Hans Joseph de Fontevieux who married a Gertrude Foelbach. We’re looking for a François de Fontevieux who married a Gertrude Foelbach. Hans Joseph is clearly not the same as François, and there may have been more than one Gertrude Foelbach.

To which I would reply, yes, there may indeed have been several Gertrude Foelbachs, of the appropriate age, in this part of France. That’s at least theoretically possible (though I have not found any). Identical names are certainly a huge problem in New England genealogy. I’ve gone down those rabbit holes more times than I can count.

But the presence of her husband’s surname, de Fontevieux, is tantalizing…and significant. Why is it significant?

As we will see in the next section, Puzzle piece No. 4, de Fontevieux turns out to be a very, very rare surname, at least at this point in French history, precisely because it was in fact made up, created, invented, fabricated – out of whole cloth – only a generation prior, and just one family, descended from one individual born about 1730, was using it– principally around Haguenau in the Bas-Rhin department of Alsace.

The creation of the name de Fontevieux for that one individual is the story that will comprise much of Puzzle piece cluster No. 4.

Puzzle piece cluster No. 4: The Aunt and the Nephew— Marianne Camasse, Countess of Forbach, and Jean-Baptiste-Georges de Fontevieux, aka the Chevalier de Fontevieux

Someone, probably Dwight Eisenhower, once said “If a problem cannot be solved, enlarge it.”

In an attempt to “widen the field of view,” I started googling the names Fontevieux and Foelbach/ Forbach/ Fülbach. If you try this, two individuals immediately come up, an aunt and a nephew. It turns out they were each in their own ways remarkable people.

Let’s start with the aunt.

Marianne Camasse, Countess of Forbach, aka Maria Johanna Francisca Camasse Gräfin von Forbach (1724 – 1807)

Marianne Camasse was the daughter of Jean Baptiste de Cammasse, or Camasse, or Cammass, or perhaps Gamache, and Eléonore Roux. Several sources describe the entire family, parents as well as children, as performers (actors, musicians, and dancers) on the Strasbourg stage.

In the 1740s, the Camasse family worked for a troupe maintained by the former king of Poland who also became the Duke of Lorraine , Stanislaus I Leszczyński, and gave shows regularly at both his chateau in Lunéville and at Versailles. In 1745, when she was eleven, Marianne performed at the Comic Opera in Paris. Her father, Jean Baptiste, died – it was rumored – in a fire in Paris, and by 1750 her mother, Eléonore, after moving the family to work in a company supported by the Elector Karl Theodor in Mannheim, had passed on too.

At any rate, at some point, Marianne caught the eye of Christian IV of Pfalz-Zweibrücken, a nobleman of considerable standing, and, after she bore him five children, on 3 September 1757, he recognized her as his morganatic wife and arranged for her to be known as, “Marianne, Countess of Forbach.” In a simultaneous effort to elevate Marianne’s relatively humble family to a status that would cause less embarrassment, the Duke also gave each of Mariannes’s brothers new (interestingly separate) surnames, and jobs at his court. More on this in a moment.

Marianne thrived in her new world, and there is ample evidence that she participated in some of the brightest and most exclusive social circles of the day. For example, she and Diderot corresponded regularly. Diderot’s 1772 work, Lettre à la comtesse de Forbach sur l’éducation des enfants was devoted to her. She was on relatively close terms with the King and Queen. And when the American Revolution got underway, she formed a solid friendship with our ambassador to France, Benjamin Franklin.

A few pieces of art, bearing on her life and times.

Source: Geni.com

Deux-Points, the town often used synonymously with both her husband and herself:

first half of the nineteenth century. Paris, private collection.]

Source: Christian IV, duc des Deux-Ponts (1722-1775): Un prince allemand francophile, « protecteur des arts » et collectionneur à Paris

Another portrait of Marianne, two of her sons, and a painting of her husband.

Source: Christian IV, duc des Deux-Ponts (1722-1775): Un prince allemand francophile, « protecteur des arts » et collectionneur à Paris

Many of the sources I’ve located to be able to relate all this are obscure: accounts of the lives of German nobility; newspaper articles from 1911; and so on. But here is a brief – non-exhaustive – list of some items you can probably find if you want to go a little further:

- Her German Wikipedia article

- The genealogy of Marianne’s husband’s family

- A short description, in English, of her relationship with Christian IV

- A long article, containing among other tidbits, speculation on the origins of Marianne’s family name(s)

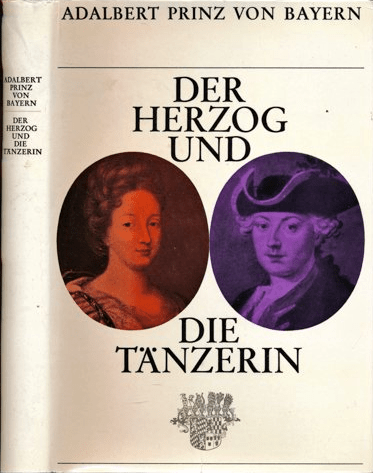

- And lastly, there is this magnum opus by Von Bayern, 1966, describing the famous relationship: Adalbert von Bayern: Der Herzog und die Tänzerin – Die merkwürdige Geschichte Christians IV. von Pfalz-Zweibrücken und seiner Familie. Pfälzische Verlagsanstalt, Neustadt an der Weinstraße 1966.

All in all, Marianne lived an extraordinary life.

Now, let’s return, briefly, to Marianne’s siblings, including her two brothers, the ones who received new surnames.

From the German Wikipedia article:

Die Geschwister der Gräfin profitierten ebenfalls von der Allianz ihrer Schwester mit dem Fürsten: Eine ältere Schwester Lolotte war als Tänzerin bekannt… Ein älterer Bruder Jean Baptiste Camasse nahm den Namen de Fontevieux an und erhielt vom Herzog den Titel eines Kommerzienrats, eine Leibrente und Wohnrecht im Schloss in Bischweiler. Ein jüngerer Bruder Pierre Camasse, ein Jugendfreund des Malers Johann Christian Mannlich, nahm den Namen de Fontenet an, erhielt den Titel eines Geheimrats…

A rough translation runs as follows:

The countess’s siblings also benefited from her sister’s alliance with the prince: an older sister Lolotte [likely “Charlotte”–LSL] was known as a dancer… An older brother Jean Baptiste Camasse took the name of de Fontevieux…[and] an annuity and right of residence in the castle in Bischweiler. A younger brother Pierre Camasse, a childhood friend of the painter Johann Christian Mannlich, took the name de Fontenet, received the title of Privy Councilor…

So, Marianne’s older brother, Jean Baptiste adopted the surname de Fontevieux, while his brother took the name de Fontenet. (I should add this information is repeated in numerous other sources. It is not in any way controversial.)

Now we’re getting somewhere. And this is a good segue to that other remarkable individual I mentioned, the nephew.

Jean-Baptiste-Georges de Fontevieux, aka the Chevalier de Fontevieux (1759-1793)

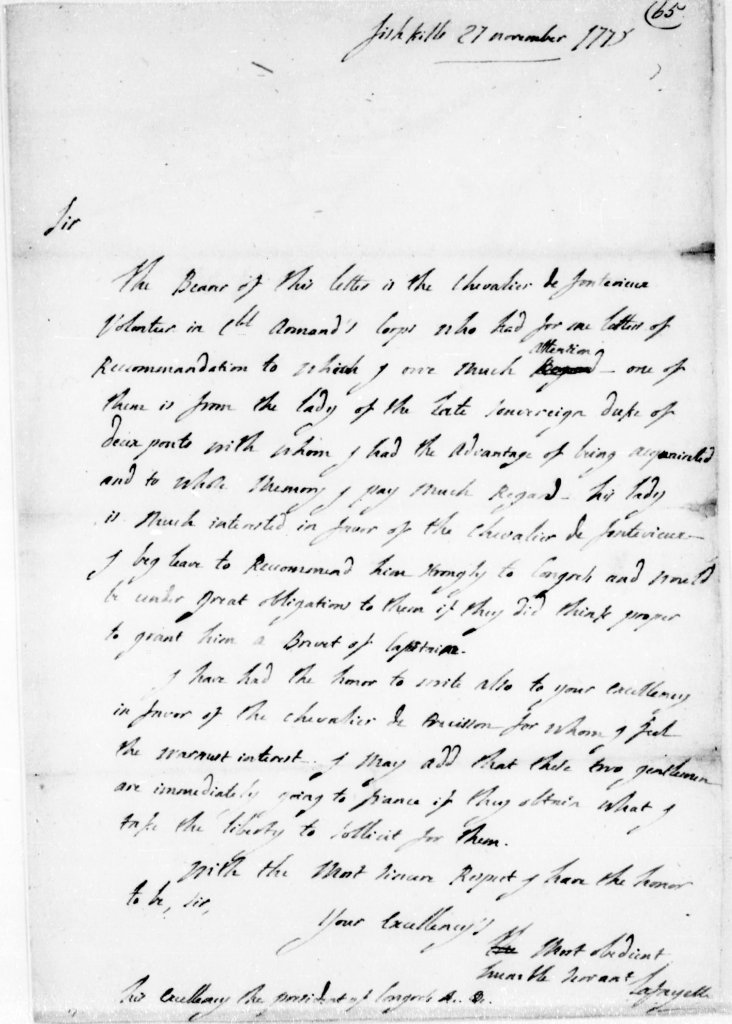

On 2 Mar 1778, Benjamin Franklin (who was in France soliciting French aid for the American Revolution) wrote George Washington to say he had been asked to pass along a request that a certain young man, Marianne, Countess Forbach’s nephew, be considered for a position in the new colonial army. Franklin, who was no fool, knew that to please the Countess was to accrue favor with her circle, and that would only be of help to America. And so he wrote…

Passy, near Paris, March 2. 1778.

Dear Sir,—M. de Fontevieux, who hopes to have the honour of delivering this into your hands, is a young Gentleman of a considerable Family, and of excellent character, who goes over with Views of improving himself in the military Art under your Auspices. He is willing to serve as Volunteer, in any Capacity for which your Excelly shall find him qualified. He is warmly recommended to me by Persons of great Distinction here, who are zealous Friends to the American Cause. And I beg leave to recommend him earnestly to your Excellency’s Protection, being confident that he will endeavour to merit it. With the greatest Esteem & Respect I have the Honour to be,

Your Excellency’s

most obedient and most humble Servant

B. Franklin

Source: Founders Online

(Also available in: Chats on Autographs by Broadley, Alexander Meyrick.)

And indeed, not long after, Marianne followed up with a letter of her own to Washington.

Sir

Suffer, my General, that I recommend to your kindness and to your protection, Mr De Fontevieux, my relation, who passed a year since into America,1 and who was then particularly recommended to you by the good and obliging Mr Franklin.2 He made the last campaign with your army attached to the corps commanded by Mr De la Rouerie, in quality of first lieutenant of dragoons—He there acquired the approbation of his chief and of the Marquis De la fayette, who, in consequence of the good testimonies which he had of his conduct, requested of you my General, the commission of Captain for him, at the moment of his embarkation to return to France.3 Permit me to join my solicitations to those of this charming protector of my young relation to obtain this rank of Captain which is the object of his wishes and mine because it will furnish him more occasions of distinguishing himself and of spilling his blood, for the justest of causes and the most interesting to humanity. The love of this cause, of its brave defenders and of the hero, who guides their valour, determined me to second the love of glory of Mr De Fontevieux, which will very soon become at home the love of country; If as I hope Sir you ⟨d⟩eign to grant your good will and obtain him that of Congress, which I dare entreat you to ask without delay, as well in your own name as in that of the person, who renders the most perfect devotion to your sublime virtues and to those of your wise legislators.4 Mr Franklin may attest to you this truth as well as the zeal the attachment to your interests of which I have made profession since the first moment of your quarrels.

Receive Sir the homage of my admiration and of all the very distinguished sentiments with which I have the honor to be My

General, Your most humble & Most Obedt servt

Contsse De Forbach

widow and dowager of the late Duke des deuxponts

Source: Founders Online

There is more interesting material on the support of the aunt, Marianne, for her nephew Georges’ adventure, both financially and morally, here and here.

In hindsight, it appears that young Jean-Baptiste-Georges de Fontevieux let no one down. He fought admirably. Also going by simply the name, “Georges Fontevieux,” he was mentioned maybe twenty times in the papers of Washington, Franklin, Hamilton, and the Continental Congress, all which I have since gotten copies of.

Here is a representative sampling of those papers.

The young man was even present at Yorktown, when Cornwallis surrendered! See NYHS v45 n01, Quarterly, January 1961 “Colonel Armand and Washington’s Cavalry.”

The Chevalier de Fontevieux’s time fighting for America was summed up in a Society of The Cincinatti publication:

Fontevieux (Jean-Georges, chevalier of), F., captain. He came from France during the summer of 1778, took service as a volunteer in the 1st battalion of the Legion of partisans, and received the praise of Rouërie and La Fayette for his conduct during the operations. Appointed lieutenant by the 1780 Congress, he was released on November 25, 1783 and promoted to United States Brevet Captain by special decision of the Congress, February 6, 1784.

Source: La société des Cincinnati de France et la guerre d’Amérique 1778-1783 by Ludovic de Contenson. Published in 1934.

Returning home, Georges de Fontevieux lived a somewhat quieter life for several years until the revolutionary fervor that he had helped to kindle on the one side of the Atlantic, and which he had served so loyally there, spread east to France.

This time, he took a rather different political view of the situation. Liberty was well and good when it meant toppling a British king. But a French king? Never.

Allying himself with his old commander from America, Armand, Georges de Fontevieux became enmeshed in a monarchist plot which was soon infiltrated by a revolutionary spy and all involved were rounded up and imprisoned.

There’s much on the web about these well-chronicled events. I won’t repeat it all. Two interesting sources are as follows:

Un agent des princes pendant la Révolution- le marquis de la Rouërie et la conjuration bretonne 1790-1793, d’après des documents inédits by Lenotre, G., 1855-1935

The chevalier also appears as a major fictional character in this book: Les aventures de Saturnin Fichet by Soulié, Frédéric, 1800-1847

Ultimately, Jean-Baptiste-Georges de Fontevieux was, like so many thousands of others, condemned to death at the guillotine. He was 34.

This appears to be the document created by the presiding body recording his sentence. It is literally his death warrant.

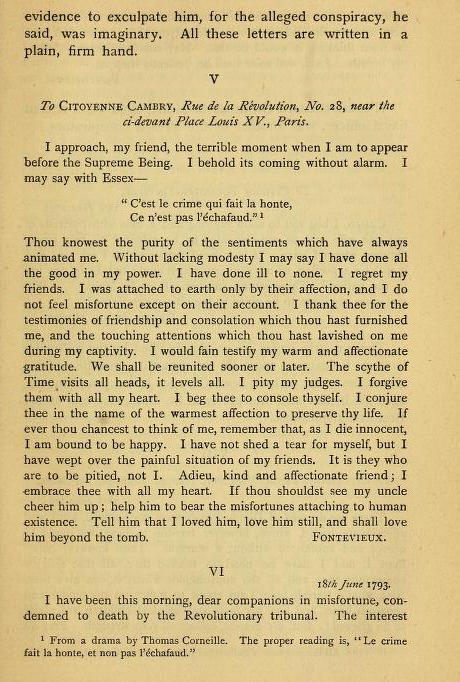

Writing from his cell, waiting for his moment to die, de Fontevieux wrote letters to the National Convention, letters to his family, a letter to his mistress, and one to his fellow prisoners. One copyright-free source reprinted two of them as follows:

A transcript:

To Citoyenne Cauchy [the spelling above is wrong–LSL],

Rue de la Revolution, No. 28, near the ci-devant Place Louis XV., Paris.

I approach, my friend, the terrible moment when I am to appear before the Supreme Being. I behold its coming without alarm. I may say with Essex —

“C’est le crime qui fait la honte, Ce n’est pas l’échafaud.”

Thou knowest the purity of the sentiments which have always animated me. Without lacking modesty I may say I have done all the good in my power. I have done ill to none. I regret my friends. I was attached to earth only by their affection, and I do not feel misfortune except on their account. I thank thee for the testimonies of friendship and consolation which thou hast furnished me, and the touching attentions which thou hast lavished on me during my captivity. I would fain testify my warm and affectionate gratitude. We shall be reunited sooner or later. The scythe of Time visits all heads, it levels all. I pity my judges. I forgive them with all my heart. I beg thee to console thyself. I conjure thee in the name of the warmest affection to preserve thy life. If ever thou chancest to think of me, remember that, as I die innocent, I am bound to be happy. I have not shed a tear for myself, but I have wept over the painful situation of my friends. It is they who are to be pitied, not I. Adieu, kind and affectionate friend; I embrace thee with all my heart. If thou shouldst see my uncle cheer him up ; help him to bear the misfortunes attaching to human existence. Tell him that I loved him, love him still, and shall love him beyond the tomb.

Fontevieux.

And:

June 1793.

I have been this morning, dear companions in misfortune, condemned to death by the Revolutionary tribunal. The interest which you have shown me and your desire to learn the judgment from my own lips induce me to inform you of it. Alas, you were far from thinking it would be this. May you fare better. Adieu, my friends. I am, and soon shall be, perfectly tranquil.

Fontevieux.

By the way, there is one other source for these, published in the modern era: Last Letters: Prisons and Prisoners of the French Revolution 1793-1794 by Olivier Blanc (NB: This book contains the letter to the National Convention, and the one cited above, to his mistress.) I have not included M. Blanc’s text here, as the work is still covered by copyright, but it contains an excellent and crisp summary of what is generally known as “La Rouërie Plot.”

You can also read more about the events, in somewhat halting English, here.

After de Fontevieux and the others were executed on the 18th of June 1793, their bodies were thrown in a mass grave, on the premises of what is today the Cimetière de Picpus, Paris, Île-de-France, France.

In 2013, a French association memorialized the event, listing M. de Fontevieux among its unfortunate victims.

18 JUIN, mais 1793

Publié le 18 juin 2013 par cultureUn vent de mort, au nom de la Liberté, a soufflé aujourd’hui sur Paris. S’ajoutent à la cinquantaine de personnes guillotinées depuis le 26 août 1792 les Membres présumés de la Conspiration du marquis de La Rouërie. En réalité il s’agit des habitants de La Guyomarais et des amis du Fondateur de l’Association Bretonne, une vaste organisation de résistance à la Révolution et au pouvoir Jacobin de la Convention.

Dans La Revue N° 35 du Souvenir Chouan de Bretagne est évoquée la personnalité hors du commun d’Armand Tuffin, marquis de La Rouërie. La liste des personnes guillotinées en ce 18 juin 1793 y est publiée.

En ce mardi 18 juin 2013, 220 ans après, jour pour jour, nous leur rendons hommage:

-Monsieur Joseph de La Motte de La Guyomarais, 49 ans,

-Madame Marie-Jeanne de La Motte de La Guyomarais, 50 ans,

-Nicolas Bernard Groult de La Motte, 63 ans,

-Thérèse de Moëlien, comtesse de Trojoliff, 29 ans,

-Jean-Baptiste Camasse de Fontevieux, 34 ans,

-Guillaume-Maurice Morin de Launay, 57 ans,

-Georges-Julien Jean Vincent, 33 ans,

-Louis-Anne du Pontavice, 25 ans,

-Félic-Victor Locquet de Grandville, 34 ans,

-Angélique-Françoise des Isles Desclos de La Fonchais, 24 ans,

-Michel-Alain Picot de Limoëlan, 59 ans,

-Thébault de La Chauvinerie.Ces condamnés par Fouquier-Tinville, lui avaient remis des lettres d’adieux (sauf messieurs de La Guyomaraus et de La Chauvinerie) pour leurs parents ou amis, ce que l’Accusateur Public ne fit jamais puisque Olivier Blanc les a retrouvées aux Archives Nationales.

Ils furent exécutés place du Trône Renversé et inhumés dans des fosses communes qui sont maintenant le cimetière de Picpus.

Leur persécuteur, Lalligand-Morillon, responsable de leur exécution sera lui-même guillotiné, pour prévarication, sur la même place et, stupéfiante ironie, inhumé dans le même cimetière de Picpus, le 7 juillet 1794, aux côtés de ceux qu’il avait contribué à faire assassiner !!!

Sur les tables mémoriales, dans la chapelle, son nom figure à leurs côtés !

Quant au docteur Chévetel – soi disant ami du marquis de La Rouërie – , le traître responsable de ces arrestations, il mourra sans son lit en 1834, après avoir été maire d’Orly.

A very rough translation goes something along these lines…

JUNE 18, but 1793

Published on June 18, 2013 by cultureA wind of death, in the name of Liberty, blew today on Paris. In addition to the 50 people guillotined since August 26, 1792 the alleged members of the conspiracy of the Marquis de La Rouërie. In reality it is about the inhabitants of La Guyomarais and the friends of the Founder of the Breton Association, a vast organization of resistance to the Revolution and the Jacobin power of the Convention.

In La Revue N ° 35 of Souvenir Chouan de Bretagne is evoked the unusual personality of Armand Tuffin, Marquis de La Rouërie. The list of persons guillotined on this 18th of June 1793 is published there.

On this Tuesday, June 18, 2013, 220 years later, to the day, we pay tribute to them:

-Joseph de La Motte de La Guyomarais, 49 years old,

-Madame Marie-Jeanne of La Motte de La Guyomarais, 50 years old,

-Nicolas Bernard Groult from La Motte, 63 years old,

-Thérèse de Moëlien, Countess of Trojoliff, 29 years old,

-Jean-Baptiste Camasse de Fontevieux, 34 years old,

-Guillaume-Maurice Morin de Launay, 57 years old,

-Georges-Julien Jean Vincent, 33 years old,

-Louis-Anne du Pontavice, 25 years old,

-Félic-Victor Locquet of Grandville, 34 years old,

-Angélique-Françoise des Isles Desclos of La Fonchais, 24 years old,

-Michel-Alain Picot Limoëlan, 59 years old,

-Thébault de La Chauvinerie.Those sentenced by Fouquier-Tinville, had given him letters of goodbye (except gentlemen of La Guyomaraus and La Chauvinerie ) for their relatives or friends, which the Public Accuser never did since Olivier Blanc found them at the National Archives .

They were executed in Throne Square thrown and buried in mass graves that are now the cemetery of Picpus.

Their persecutor, Lalligand-Morillon, responsible for their execution will himself be guillotined, for prevarication, on the same place and, stupefying irony, buried in the same cemetery of Picpus, July 7, 1794, alongside those he had helped to murder !!!

On the memorial tables, in the chapel, his name is on their side!

As for Doctor Chévetel – so-called friend of the Marquis de La Rouërie – the traitor responsible for these arrests, he died without his bed in 1834, after being mayor of Orly.

Joining the pieces (however tentatively)

Now that we have viewed the puzzle pieces laid out, let’s see how they might connect. Let’s start by going back to Marianne’s older brother.

From the German Wikipedia article on Marianne, and indeed from multiple other sources, we learned that following Marianne’s marriage, and her ascendance to the nobility, her brothers too were given noble surnames…individual noble surnames.

Her older brother became Jean Baptiste Camasse de Fontevieux, and her younger brother became Pierre Camasse de Fontenet.

There’s been speculation by various authors regarding the source of the adopted name de Fontevieux. The consensus seems to be it was created more or less de novo. One researcher stated flatly it follows none of the usual rules. Another thought it was a variation on Fontenet or something close to that. Yet another stated it may have related to a small piece of land the family once owned. Interestingly, in court documents from 1776, likely provided by Marianne, it was said that de Fontevieux was the name of the family when they had lived in Spain, but the father, Jean Baptiste was forced to hide his identity and adopted Camasse or de Camasse. What is the truth? I’m not sure anyone really knows.

At any rate— regardless of how many sons these two brothers may have ultimately had, we know that any male in that area of France and/or Prussia bearing the surname de Fontevieux, and born in the era immediately following Marianne’s marriage to the Duke, was almost certainly a son of Jean Baptiste Camasse de Fontevieux.

It turns out we also know a few more things about Jean Baptiste’s domestic life. He married a woman named Maria Helena Chesal and had 21 children, with eleven surviving to adulthood. (Amazing. The thought of burying ten children is not something we in the modern era could ever contemplate, much less get through.)

From a book called Jahr-Buch der Gesellschaft für lothringische Geschichte und Altertumskunde, put out by the Société d’histoire et d’archéologie de Lorraine in 1912, we learn the following.

…Offenbar ist dieser Jean Baptiste nicht der Vater, sondern ein Bruder Mariannens; denn er heiratet am 3. Juli 1750 zu Mannheim die Maria Helena Chesal, Mainzer Diozese (gütige Auskunft des katholischen oberen Stadtpfarramts zu Mannheim) und hatte mit ihr 21 Kinder, von denen im Jahre 1771 noch 11 lebten. Jean Baptiste kommt seit 1764–1781 zu Hagenau und Bischweiler als herzoglicher Agent und Kommerzienrat unter dem Namen de Fontevieux vor. Culman bezeichnet ihn als Bruder der Grâfin Forbach. Daû dieser Jean Baptiste de Fontevieux mit dem Mannheimer Schauspieler Jean Baptiste Camasse identisch ist, wird durch…Zu allem UberHuG nennt er sich in einem Akte des Straûburger Bezirksarchivs (Ei 1718 Sept. 16) Jean Baptiste Camasse de Fontevieux…

A rough translation:

…Apparently this Jean Baptiste is not the father but a brother of Marianne; because he marries on July 3, 1750 to Mannheim [resident] Maria Helena Chesal, Mainzer Diozese …and had with her 21 children, of which in 1771 11 still lived. Jean Baptiste comes since 1764-1781 to Hagenau and Bischweiler as a ducal agent and councilor under the name de Fontevieux. Culman calls him brother of Grâfin Forbach. This Jean Baptiste de Fontevieux is identical to the Mannheimer actor Jean Baptiste Camasse… To top it all off he calls himself Jean Baptiste Camasse de Fontevieux in a file of the Stralsburger district archives (Ei 1718 Sept. 16).

Since Jean-Baptiste-Georges de Fontevieux, the soldier of the American Revolution, was guillotined at the age of 34 in 1793, we know he was born circa 1759.

We also know “Georges” was the nephew of Marianne, Countess Forbach. Given, as I’ve emphasized, that only Marianne’s older brother Jean-Baptiste took the surname de Fontevieux, it seems almost certain that Jean-Baptiste-Georges de Fontevieux, aka the Chevalier Fontevieux, was in fact the son of Jean-Baptiste Camasse de Fontevieux, Marianne’s older brother.

At this point I’ll introduce a text that has proved instrumental to me, in really understanding the larger Camasse/ de Fontevieux family, and that is a work by a gentleman named Walter Petto, which I would not have had access to were it not for the kindness and generosity of Roland Geiger, of the Association for Saarland Family Studies (http://saar-genealogie.de/).

Walter Petto: Die Herkunft von Marianne Camasse, Gräfin von Forbach, und ihrer Geschwister. In: Saarländische Familienkunde. Band 9, Saarbrücken 2002, S. 63–90.

(translation)

Walter Petto: “The origin of Marianne Camasse, Countess of Forbach, and her siblings.” In: Saarland family history. Volume 9, Saarbrücken 2002, p. 63-90.

Since I don’t know the ins and outs of German copyright law, I don’t want to tempt fate by reproducing any of the article here, even what would be allowed under U.S. “fair use” rules. But it’s an excellent portrait of the circumstances behind Marianne’s romance with the Duke, the fate of her sisters, especially “Lolotte” or Charlotte, the life lived at court by her brother Pierre, and – yes! – a brief account of her older brother, Jean Baptiste Camasse de Fontevieux and his family.

Essentially, Petto writes that Jean Baptiste (born c. 1730) was a man who, despite a generous allowance from his brother-in-law, nevertheless lived a dissolute life, and near the end of that life had little reputation left to salvage. Petto states it is “probable” that Jean-Baptiste-Georges, the Chevalier de Fontevieux, was his son.

This would certainly explain both the young man’s zeal to make a positive name for himself in a foreign war for independence, and also why it was his very well-connected aunt who was interceding on his behalf with Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, and others.

To my knowledge, and I’ve been reading just about everything out there on this family, Petto is the first scholar to clearly come out and assign a likely father for the young soldier. But, as I think I’ve shown, his guess makes complete sense, and is well supported by the facts we do know.

OK, let’s now cut to a different section of the puzzle…the question we more or less started with: the origin of Jean de Fontevieux’s (1798-1832) father, François, and his mother, Gertrude Foelbach.

Recall that, per the passages quoted above, in the Jahr-Buch der Gesellschaft für lothringische Geschichte und Altertumskunde, Marianne’s older brother, Jean Baptiste (b. 1730), was living in Haguenau between 1764-1781.

Recall also that the husband of the Gertrude Foelbach mentioned in the marriage data from FamilySearch, added there in 2012, the so-called “Hans Joseph de Fontevieux,” was, according to FamilySearch, born in Hagenau about 1769.

Now, I couldn’t find a reference for a “Hans Joseph de Fontevieux” born in Haguenau, or anywhere else, but I did find the birth record of one “François Joseph de Fontevieux,” born in Hagenau, on the 7th of June, 1768.

BIRTH

City/Town Code : 67180

Place : Haguenau

State/County/Subdivision Code : 67

Subdivision : Bas-Rhin

Type : N

Date : 07/06/1768 (7 June 1768)

Last Name : FONTEVIEUX (DE)

First Name : François Joseph

Hmm. That’s intriguing. Marianne’s brother, Jean-Baptiste Camasse de Fontevieux (born c. 1730) was living in Hagenau c. 1768. And at that point he’s the only male we know of with that particular surname. A boy named François Joseph de Fontevieux was born in Hagenau in 1768. And this is the same first name or Christian name as that of Jean’s father– the man who married Jean’s mother, Gertrude Foelbach. Put this together with the assertion, perhaps correct, perhaps incorrect, that in a town not too far away, a man named Hans Joseph de Fontevieux married a woman named Gertrude Foelbach, in just the right time frame. Could this difference between the two names just be down to a transcription error of some kind? It seems a highly unlikely coincidence. Two men, with identical middle names and last names, probably from a single father who created that name, marrying two separate women also with the same name? As the fictional character Jack Ryan says in Tom Clancy’s film, Patriot Games:

Admiral Greer: What do you think, same guy?.

Ryan: The rare-book dealer, Dennis Cooley.

Patriot Games

He’s bald.

It’s possible there’s a woman

in some of these camps.

But with her and Cooley

in the same place …

… if that is Cooley, the odds

of coincidence are dropping fast.

But still,

there’s no way I can be …

… absolutely certain.

One last item of note.

François Joseph de Fontevieux, the putative husband of Gertrude Foelbach, and father of Jean, appears to have been born in or around Haguenau. Jean de Fontevieux was said to have been born in or grown up in Oberdorf. So by extension, we can surmise that his parents, who we know were named François de Fontevieux and Gertrude Foelbach, were living, at least for a time, in Oberdorf.

Is there anything to be gleaned from this?

Stepping away from Google Translate, and clicking on Google Maps, I got a small surprise.

It turns out, Haguenau is actually only fifteen km from Oberdorf-Spachbach!

The possible father, and the known son, were each born a stone’s throw from each other.

Like the line in the film says, “The odds of coincidence are dropping fast. But still, there’s no way I can be absolutely certain.”

It’s not proof. It’s a circumstantial case, but an increasingly powerful one.

Assembling everything we’ve discussed so far, here is my proposed genealogy for this family:

Jean Baptiste Camasse (1704 – abt 1748) & Eleonore Roux (1704 – abt 1750)

| Marie Salomée Camasse (abt 1726 – )

| Charlotte “Lolotte” Camasse (15 Sep 1728 – bef Jul 1769) & Jacques Charles Ribon (12 Jun 1724 – 7 Mar 1782)

| Jean Baptiste Camasse de Fontevieux (abt 1730 – ) & Maria Helena Chesal (abt 1732 – )

| | Carl Jacob Camasse de Fontevieux (abt 1751 – ) & Salomée Ruiliard; also & Maria Petronella de Thoré (abt 1755 – )

| | Maria Stephana Camasse de Fontevieux (Apr 1752 – )

| | François Étienne Camasse de Fontevieux (Mar 1753 – )

| | Jean-Baptiste-Georges “Georges” Camasse de Fontevieux, “Chevalier Fontevieux” (abt 1759 – 18 Jun 1793) & Caroline de Lüder

| | | Carolina de Fontevieux (8 Apr 1793 – )

| | François Joseph (possibly “Hans Joseph”) de Fontevieux (7 Jun 1768 – ) & Gertrude Foelbach (2 May 1773 – aft 1798)

| | | Jean de Fontevieux (abt 1798 – 18 Jan 1832) & Aimée Véronique Legrand (17 Dec 1797 – 16 Mar 1871)

| | | | Pauline Gertrude de Fontevieux (23 Mar 1819 – 7 May 1886) & Hon. William McKennan (27 Sep 1816 – 27 Oct 1893)

| | | | | Isabel Bowman McKennan (10 Oct 1843 – 5 Dec 1891) & Maj. George McCully Laughlin (21 Oct 1842 – 11 Dec 1908)

| | | | | | Irwin Boyle Laughlin (26 Apr 1871 – 18 Apr 1941)

| | | | | | George McCully Laughlin Jr. (25 Feb 1873 – 9 Mar 1946)

| | | | | | Thomas McKennan Laughlin (16 Mar 1875 – 29 Apr 1936)

| | | | | | William McKennan Laughlin (31 May 1876 – )

| | | | | | Pauline Gertrude Laughlin (21 Sep 1877 – 29 Jun 1880)

| | | | | Thomas McKean Thompson McKennan (21 Mar 1845 – 8 Feb 1920) & Laura Belle Cunningham (27 Dec 1851 – 20 May 1914)

| | | | | Emma Willard McKennan (5 Nov 1846 – 31 Aug 1879) & William Wrenshall Smith (15 Aug 1830 – 4 Aug 1904)

| | | | | | William McKennan Smith (2 Jul 1868 – 16 Oct 1948)

| | | | | | Ulysses Simpson Grant Smith (18 Nov 1870 – 1959)

| | | | | Henry Sweitzer McKennan (18 Oct 1848 – 9 Jan 1889)

| | | | | Samuel Cunningham McKennan (8 Jul 1850 – 10 Sep 1895)

| | | | | John De Fontevieux McKennan (12 May 1854 – 2 Feb 1912)

| | | | | Gertrude Marie McKennan (11 Feb 1856 – 11 Nov 1935) & William Murray LeMoyne (29 Jun 1855 – 16 May 1931)

| | | | | Anne Viola McKennan (30 Dec 1858 – 19 Apr 1934) & Alexander Williams Biddle (4 Jul 1856 – 19 Sep 1916)

| | | | | | Pauline Biddle (7 Aug 1880 – Feb 1968)

| | | | | | Christine A Biddle (20 Oct 1882 – )

| | | | | | Julia Rush Biddle (16 Aug 1886 – 31 Dec 1978) & Thomas Charlton Henry (24 Mar 1887 – 24 Jan 1936)

| | | | | | Isabel Biddle (16 Jan 1888 – 1953)

| | | | | | Alexander Biddle (4 Apr 1893 – 6 Feb 1973)

| | | | | David Wilson McKennan (10 Apr 1860 – 5 Dec 1893)

| | | | | William McKennan Jr. (30 Oct 1862 – 25 Jan 1917)

| | | | Charles Valentin de Fontevieux (6 Nov 1821 – )

| | | | Joseph Alexandre de Fontevieux (20 Oct 1822 – )

| | | | Gertrude Joséphine de Fontevieux* (4 Jan 1824 – ) & Louis Alexandre Grand (10 Feb 1819 – 7 Mar 1851)

| | | | | Aimé Maria Grand (29 Feb 1844 – ) & Jules Ferdinand Levasseur (1835 – )

| | | | | Maurice Alexandre Grand (11 Mar 1846 – 23 Feb 1851)

| | | | Gertrude Joséphine de Fontevieux* (4 Jan 1824 – ) & Pierre Hyacinthe Rebours (15 Sep 1822 – 15 Nov 1871)

| | | | | Pierre Hyacinthe Rebours (4 Apr 1855 – ) & Catherine Louise Maria Basia (3 Apr 1856 – )

| | | | Eugène Jean de Fontevieux (18 Feb 1832 – 5 Apr 1903) & Marie Borde or Bordes (22 Jan 1838 – )

| | | | | Estelle Joséphine de Fontevieux & Jean Baptiste Bocognano

| | | | | Aimé Marie de Fontevieux (26 Mar 1859 – )

| Franciscus Henricus Camasse (22 Feb 1732 – )

| Johannes Elisabeth Camasse (Apr 1733 – 1733)

| Maria Johanna Francisca Camasse Gräfin von Forbach (2 Sep 1734 – 1 Dec 1807) & Christian IV von Zweibrücken-Birkenfeld Herzog von Pfalz-Zweibrücken (6 Sep 1722 – 5 Nov 1775)

| | Christian von Birkenfeld-Bischweiler (Forbach) (20 Sep 1752 – 25 Oct 1817)

| | Philipe Wilhelm of Wittelsbach Count of Forbach, Viscount of Deux-Ponts (18 Jun 1754 – 21 Jul 1807)

| | Maria Anna Caroline von Zweibrücken (28 Jun 1755 – 4 Aug 1806)

| | Karl Ludwig of Wittelsbach Baron of Zweibrucken (1759 – 1763)

| | Elisabeth Auguste Friederike von Zweibrücken (6 Feb 1766 – 14 Apr 1836)

| | Julius August Maximilian of Wittelsbach Baron of Zweibrucken (1771 – 1773)

| Pierre Camasse de Fontenet (30 Aug 1737 – 9 May 1809)

As things stand, we are left with three questions the answers to which could really nail all this down. (Those answers will likely come from local records obtained within the Alsace region itself, or some digital compendium of those records.)

- Did Jean Baptiste Camasse de Fontevieux (1730-?), father of the Chevalier de Fontevieux, have another son named François Joseph de Fontevieux, born in June 1768 in Haguenau?

- And if so, was that the same François Joseph (perhaps confused as Hans Joseph) de Fontevieux who married Gertrude Foelbach in 1796 in Kadenbach, Hessen-Nassau, Preussen/ modern-day Germany?

- And if so, was he also the same François de Fontevieux who, along with his wife, Gertrude Foelbach, may have lived for a time in Oberdorf-Spachbach and who – possibly(!) – named his son, Jean de Fontevieux (1798-1832), after his valiant dead brother, Jean-Baptiste-Georges, the Chevalier de Fontevieux, the devoted friend of the American Revolution who had been guillotined in the Terror just five years earlier?

Time will tell…or, it won’t.

My apologies to future researchers who discover any mistakes I may have made.

And a hope that somewhere, somehow, Pauline Gertrude (de Fontevieux) McKennan recognizes that people are still telling the stories of the complex and (to me) utterly compelling family she left behind when, as a girl of 13, she took Emma Willard’s hand and sailed for America.

_____