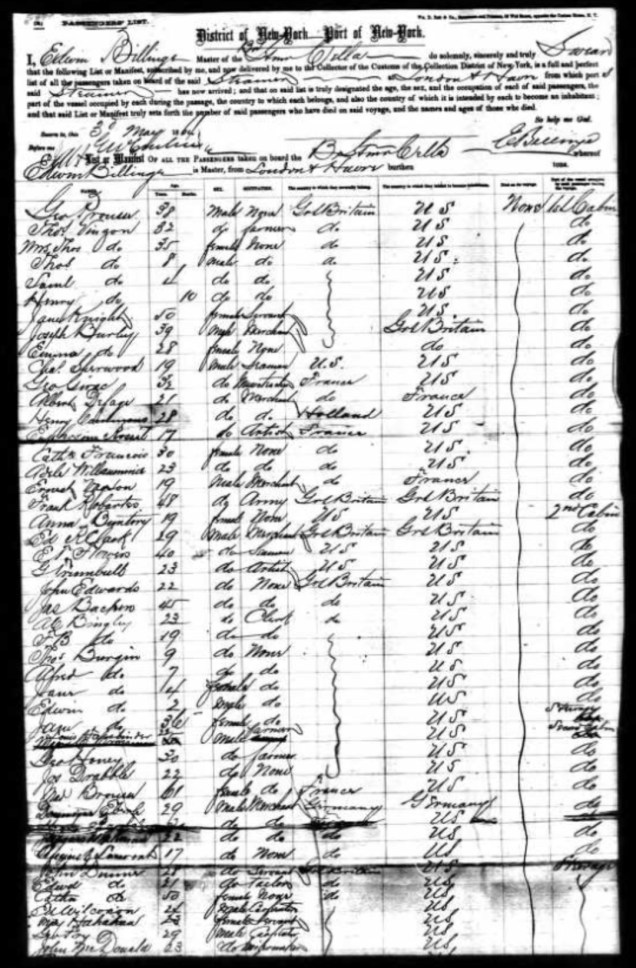

In a period when the idea of immigration as a fundamental aspect of the American experience is on a lot of our minds, it was somewhat dumb luck that I happened across something we’ve been looking for for a long time: the (probable) record of the arrival of Jane Skudder Burgin and her children, via the steamship Cella, Edwin Billings master, in the port of New York from London, May 3, 1864.

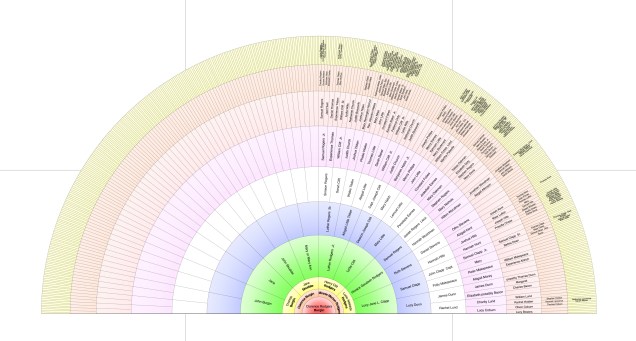

These were the last/ most recent people in our family to leave their country, their friends their family, and most of their belongings, and come here.

(Off topic, but worth mentioning, it would take just eight years for Thomas Burgin to apply for and be granted his first patent.)

Looking at this list, I feel I was – almost – there to greet them.

And I suppose the larger point is worth making… Let’s continue to do everything we can to make the people coming today feel equally welcome and equally capable.

______

A transcription of the basic information is as follows:

Arrival Date: 3 May 1864

Family Ethnicity/ Nationality: British (English)

Place of Origin: Great Britain

Port of Departure: Le Havre, France and London, England

Destination: United States of America

Port of Arrival: New York, New York

Ship Name: Cella